What's Counterbound for?

Magazines, a holiday party, and a question about this newsletter —

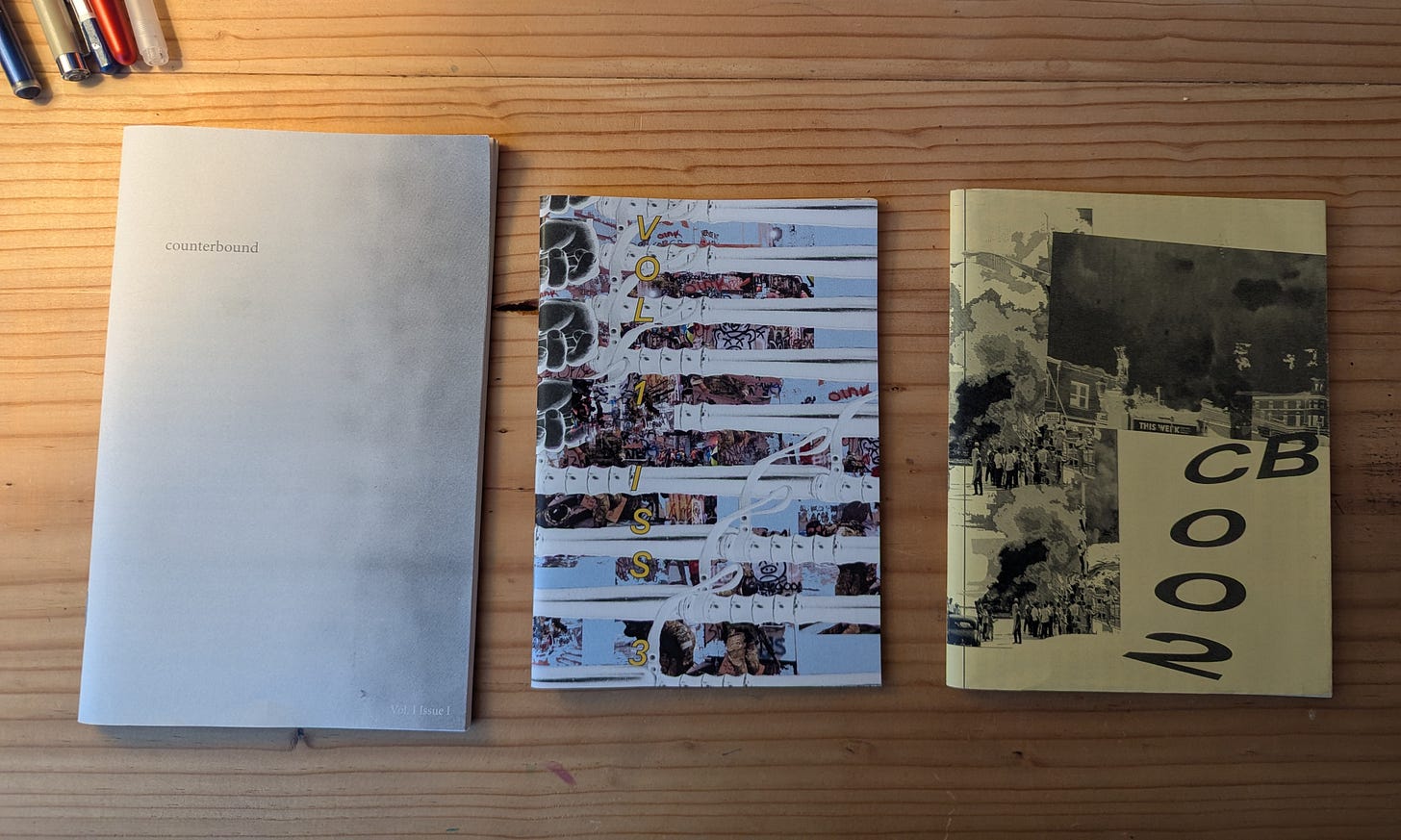

The other day, I pulled the third edition of the original Counterbound off my shelf, a small monthly magazine that my friends and I published four years ago, in 2020. Over those six months or so, we ran four editions and an art book for a photographer in the Willamette Valley. We all did a bit of everything. Trevor Warren took on art and design and Sam Becker helped edit, research, and publish. The experience was formative for all of us. Trevor is now a painter and Sam does great work FOIA’ing local government as a researcher with Information for Public Use.

Perhaps most important for all of us during those six months of making a magazine was learning really quickly what it was like to take something public. That is, what it meant to make something both relevant to an audience and sustainable enough that those involved wanted to continue to work on it.

It was ambitious and a lot of hard work, and, for that reason, I love these small magazines a lot. Even if we hit all after wall (burnout, being ‘in-the-red’ constantly). In their own way, the books are a time capsule of an insane year. There was COVID, uprisings against the police, and, if you lived in the Rogue Valley at the time, the Almeda Fire.

We still managed to put art and writing from people from the Rogue Valley into a book, which people then bought.

Now, I’ve started this newsletter. It, at the very least, shares the same name and some of the original spirit. As was the case back then, my main goal is to make this both relevant to this audience and sustainable enough that I can continue to work on it.

At a holiday party, a friend asked me about my next post on Counterbound. When was it coming? What was I working on? I laughed. It had been a few weeks since I wrote my first reported story on this platform about the Neo-Nazi in Coos Bay. Self employed, I was on my own timeline. I told him I had a few ideas and wanted to keep doing journalism that was not getting enough coverage, but reporting was taking a while. He’d subscribed (to my delight). Needing an excuse for my inability to publish, I conjured up the first excuse that came to mind. “I guess I’m a bad business man!” I joked, pained.

In a moment of care, he told me he’d like to read a post soon, even if it wasn’t investigative reporting. “Just write something.”

This was great advice, thanks, Bill.

So here is my plan. In order to keep this sustainable, I won’t necessarily bring you a reported story every two to three weeks. I want to, but I am in the throes of finishing a documentary (I’ll write about that in another post).

Instead, I’d like to share with you a two ideas that I am working on for Counterbound. That way, I can keep this relevant to you and sustainable for me.

Here they are:

Renewable energy in the Klamath Basin.

In December, I attended a screening of These Sacred Hills, a documentary about the Rock Creek Band of the Yakima Nation and, as Toastie Oaster at High Country News has detailed in their excellent reporting, the deluge of renewable energy projects threatening areas critical to their culture and way of life in the Columbia River Basin, like food gathering and a mountain named Pushpum. Toastie and I went to a screening at the Yakima Nation’s winter lodge in Topponish, Washington, where Yakama Nation Tribal Councilman Jeremy Takala noted that something similar happening in Klamath Falls at Swan Lake.

There, “pumped hydro-storage” (basically an energy storage technology made with two reservoirs full of water) is being built by the same corporation.

“We are very pro renewable energy,” the Klamath Tribes Chairman Clayton Dumont told NBC5 back in October. “We have been hurt badly by global warming so we support that. The problem is where this project is going to go.”

An update on the ACLU’s class action lawsuit against Siskiyou County

Back in October, in an ongoing class action lawsuit over racial discrimination in Siskiyou, a District Court in California granted a temporary “preliminary injunction.” Basically, they stopped the county from enforcing certain zoning ordinances designed to prevent well owners from filling water trucks.

The lawsuit, representing mostly Hmong residents of the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision, alleges recent zoning enforcement “deprived them of the water they need to cook, drink, bathe, wash clothes, grow food, raise animals and fight fires.” All in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause.

I started reporting on this back in 2020, and since then, the fight over water and land use in Siskiyou County has continued. The government wants to limit water to a part of the county where Hmong people live and farm cannabis. There, they face water shutoffs, racial profiling, near weekly raids, and constant police surveillance.

It’s the subject of my upcoming film. But in the meantime, I want to at least give an update and some context to the legal fight happening just over Oregon’s southern border.

Until then!